I’ve started several Python projects this year, all using the same Copier template. Each time, Copier generates the structure: pyproject.toml, pre-commit config, Makefile, the usual suspects. But here’s what makes Copier different: when I improve the template, all projects can pull in those improvements automatically.

This workflow has saved me countless hours. I restructured how I handle configuration files across all my projects. Instead of manually updating all codebases, I changed the template once and ran copier update in each project. The improvements propagated in minutes and those projects aren’t diverging into slightly different configurations. They’re staying consistent because the template keeps them that way.

Most developers treat templates as scaffolding. Generate the project, walk away, never look back. Cookiecutter has been the go-to tool for this approach for years, and it works fine for that model. But here’s the thing: your practices improve over time. You learn better patterns. You discover better tools. And suddenly, every project you’ve ever created is stuck in the past.

Copier flips this model. Templates aren’t one-time scaffolding. They’re living contracts between your current best practices and your existing projects. When the template evolves, your projects can evolve with it. That’s the workflow shift that matters, and I’ll show you exactly how it works using my Copier template as an example.

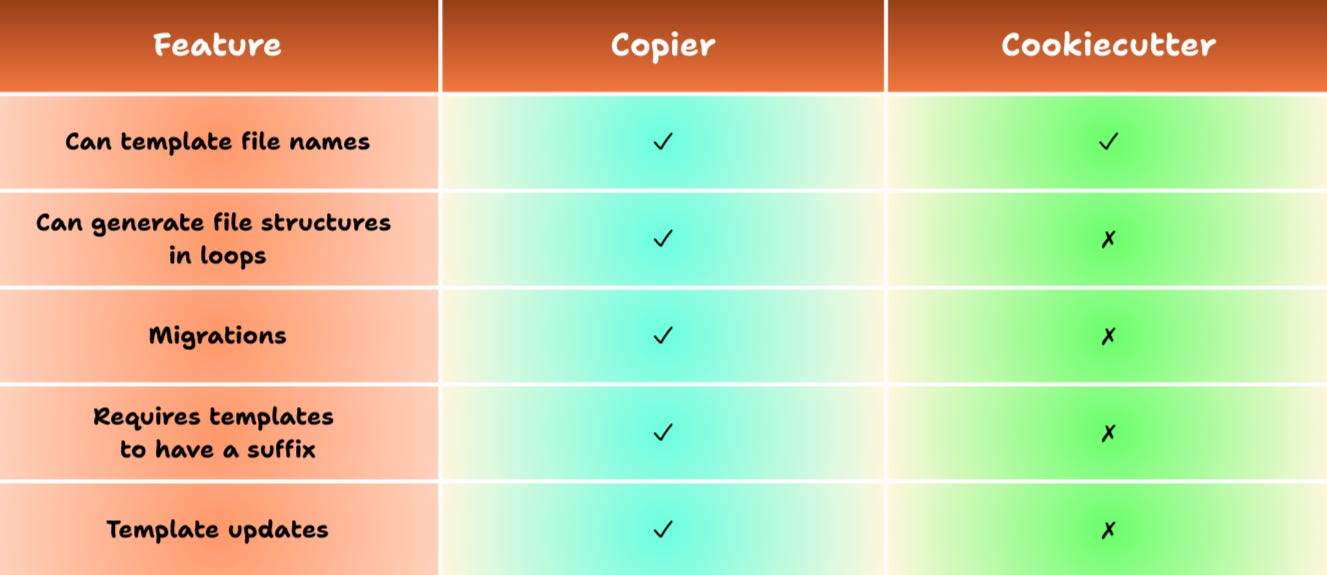

From Static to Dynamic: How Copier Improves on Cookiecutter

Cookiecutter generates projects beautifully. You answer some questions, it creates a folder structure with all your files, and you’re coding in minutes. I used it many times. The problem surfaces later.

Let’s say you’ve created five projects with your Cookiecutter template. Then you discover prek—a faster, Rust-based alternative to pre-commit—and realize every project should use it. With Cookiecutter, you have two options: manually add it to all five projects, or accept that new projects will have it but old ones won’t. Neither option is great.

Copier solves this with a simple command: copier update. It pulls the latest template changes, compares them against your project’s version, and intelligently merges the differences. Conflicts get flagged. You review, accept, or reject changes, and move on. The template improvement propagates to every project that wants it.

This isn’t just about adding tools. It’s about fixing mistakes too. When I realized my mypy configuration was too permissive, I tightened it in the template. One update command later, all my projects had stricter type checking. No manual file editing. No copying configs between projects.

The decision to switch came down to a simple question: Do I want to maintain projects, or do I want to maintain one template and let it maintain the projects?

Building a Template That Does More Than Generate Files

The heart of a Copier template is copier.yml. This file defines the questions to ask, the variables to create, and the tasks to run after generation. Here’s the core structure I landed on:

# copier.yml

_templates_suffix: .jinja

_src_path: “{{ _copier_conf.src_path }}”

_tasks:

- “cp env.example .env”

- “rm -rf env.example”

- “git init”

- “git add .”

- “git commit -m ‘Initial commit’”

- “gh repo create {{ project_name }} --source=. --private --push --remote=origin”

- “uv sync --all-groups”

- “uv add --group test pytest”

- “uv add --group lint ruff mypy”

- “uv add --group dev prek”

- “make tests || true”

- “git add .”

- “git commit -m ‘Setup development dependencies and tooling’”

- “git push”

- “echo ‘Project {{ project_name }} generated successfully!’”

# Questions to ask when generating a new project

project_name:

type: str

default: “awesome-ai-app”

help: “The name of your new project”

module_name:

type: str

default: “{{ project_name | lower | replace(’-’, ‘_’) }}”

help: “Python module name for your application (used in src/...)”

description:

type: str

default: “A basic project generated from the template”

help: “Short description of your project”

version:

type: str

default: “0.1.0”

help: “Initial version of the project”

python_version:

type: str

help: “Python version used in Dockerfile and virtual environment”

choices: [”3.14”, “3.13”, “3.12”]

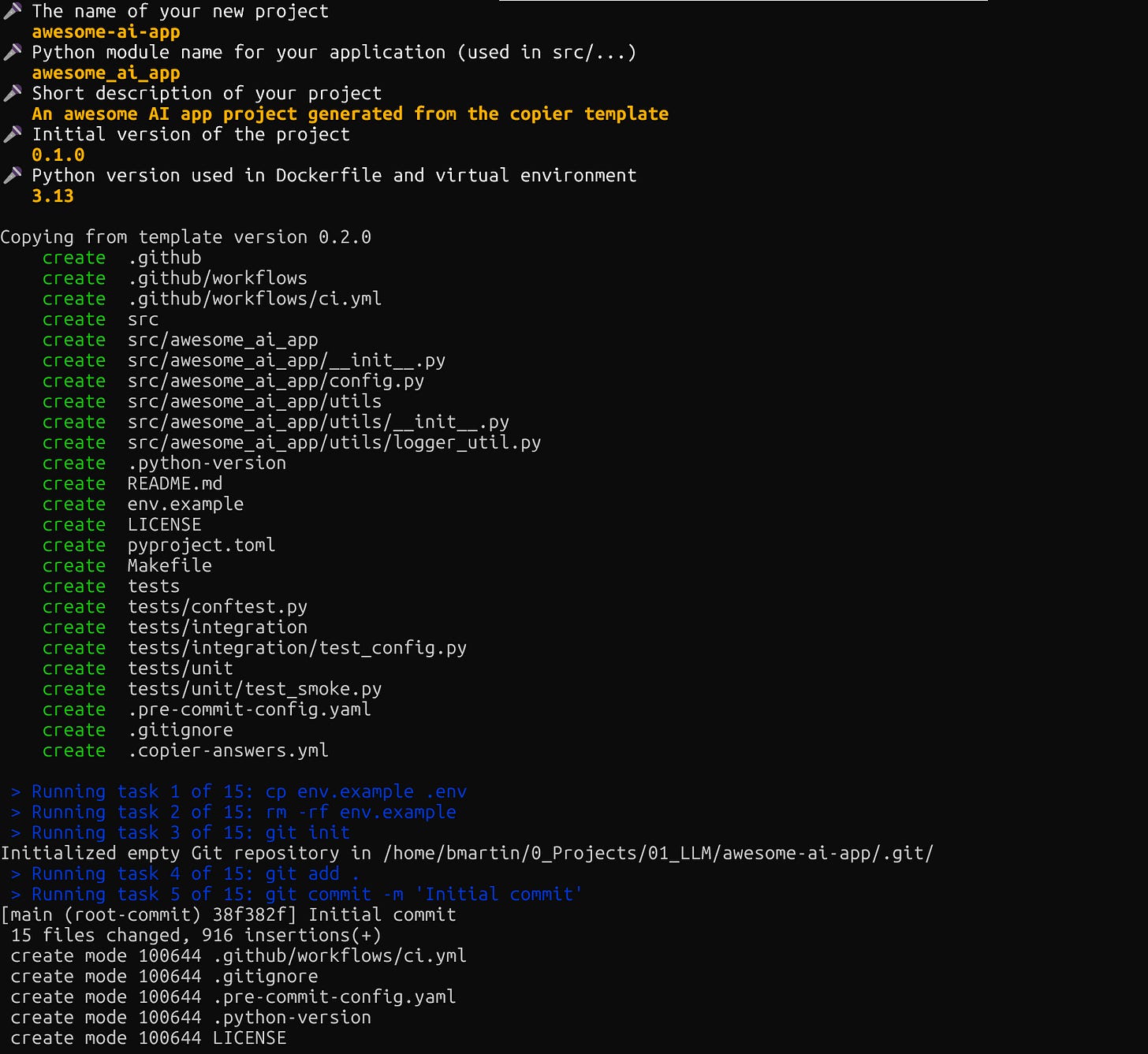

default: “3.13”The _tasks section is where Copier shows its power. These aren’t just file generation steps—they’re actual commands that run after your project is created. The template doesn’t just create a git repository; it initializes it, makes the first commit, and pushes it to GitHub. It doesn’t just write a pyproject.toml; it installs all dependencies and runs your test suite.

This was a revelation. With Cookiecutter, you generate files and then manually run a bunch of setup commands. With Copier, those commands are part of the template. New project? Two minutes from running the template to having a fully initialized, tested, version-controlled repository pushed to GitHub.

The Jinja templating is where variables flow through your entire project structure. When someone answers project_name: “awesome-ai-app”, that value propagates everywhere. The GitHub repo gets that name. The README gets that title. But it also transforms: module_name becomes awesome_ai_app (replacing hyphens with underscores for Python compatibility), and that determines the folder structure in src/.

Here’s what the generated structure looks like:

.

├── .github

│ └── workflows

│ └── ci.yml

├── LICENSE

├── Makefile

├── README.md.jinja

├── copier.yml

├── env.example

├── pyproject.toml.jinja

├── src

│ └── {{ module_name }}

│ ├── __init__.py

│ ├── config.py

│ └── utils

│ ├── __init__.py

│ └── logger_util.py

└── tests

├── conftest.py

├── integration

│ └── test_config.py.jinja

└── unit

└── test_smoke.pyEvery file that needs customization gets the .jinja suffix in the template. So pyproject.toml.jinja becomes pyproject.toml with all variables substituted. The README is dynamic based on the project name and description. Even the Python version in .python-version comes from the question you answered.

The pyproject.toml.jinja file is particularly interesting because it shows how to template entire dependency blocks:

[project]

name = “{{ project_name }}”

version = “{{ version }}”

description = “{{ description }}”

readme = “README.md”

authors = [

{name = “Benito Martin”}

]

license = {text = “{{ license }}”}

requires-python = “>={{ python_version }}”

dependencies = []

[dependency-groups]

dev = []

lint = []

test = []When you generate a project, those variables get filled in. But the template also includes commented examples for common dependencies such as PyTorch with CPU-only wheels. You uncomment what you need, and the next uv sync pulls them in.

The template includes one critical file that enables the update workflow: .copier-answers.yml.jinja. This file tells Copier to create an answers file in every generated project:

# .copier-answers.yml.jinja

{{ _copier_answers | to_nice_yaml }}When Copier generates a project, it replaces {{ _copier_answers | to_nice_yaml }} with the actual metadata—template source, version, and your answers. Without this file in your template, the answers file won’t be created, and updates won’t work. It’s small but essential.

The Makefile provides a consistent interface across all projects. make tests runs pytest. make all-check runs ruff format checks, ruff linting, and mypy. make all-fix auto-fixes what it can. Every project I generate has the same commands, so muscle memory works everywhere.

I learned some things the hard way during template development. In my first attempt, I included too many questions. I stripped it back to essentials: project name, module name, Python version, and description. Everything else has sensible defaults you can change later.

When Templates Evolve, Projects Can Too

Here’s where Copier’s value becomes undeniable. A few weeks ago, after working on several projects with my template, I discovered prek, a faster, Rust-based alternative to pre-commit that I wrote about recently. I wanted to add it to all my projects. In the template, I added this to the _tasks section in copier.yml, to my Makefile and also to the .pre-commit-config.yaml file:

_tasks:

# ... other tasks

- “uv add --group dev prek”

- “uv run prek install”Then I committed, tagged the new version, and pushed:

git add .

git commit -m “feat: Add prek for faster pre-commit hooks”

git tag v0.2.0

git push origin main --tagsNote: you must have this to be able to run

copier update:

The destination folder includes a valid

.copier-answers.ymlfile.The template is versioned with Git (with tags).

The destination folder is versioned with Git.

Now I went into each existing project and ran copier update --trust --skip-tasks. Copier compared the template’s copier.yml against each project’s version, saw the new prek setup, and asked if I wanted to merge it. I reviewed the diff, accepted the change, and committed. All my projects were updated in about ten minutes.

The --skip-tasks flag prevents the _tasks from running during updates. Those tasks (git init, GitHub repo creation, dependency installation) make sense during initial project generation but not during updates. Without this flag, Copier would try to create the GitHub repository again, which fails because it already exists.

The update workflow preserves your project-specific changes. If you’ve added custom pre-commit hooks, Copier merges the template’s new hooks alongside yours. If you’ve modified the Makefile with project-specific commands, those stay while template improvements merge in.

This is tracked through .copier-answers.yml, which every generated project includes. It looks like this:

_commit: v0.1.0

_src_path: gh:benitomartin/copier-template

project_name: awesome-ai-app

module_name: awesome_ai_app

description: A basic project generated from the template

version: 0.1.0

python_version: “3.13”When you run copier update, it knows which template version generated your project and what answers you gave. It fetches the latest template, compares files, and intelligently merges changes. You’re not re-answering questions unless new ones were added to the template.

The merge interface uses standard git-style conflict markers. When Copier can’t automatically merge changes, it inserts conflict markers directly into the file. You open the file in your editor, decide which changes to keep, remove the conflict markers, and save. It’s exactly like resolving a git merge conflict.

What really surprised me was how this changed my relationship with project maintenance. Before Copier, I’d avoid improving my boilerplate because propagating changes was painful. Now I actively refine the template. Better logging utility? Add it to the template, update projects when convenient. Discovered a useful pre-commit hook? Same process. The friction is low enough that I actually do it.

There’s a psychological shift too. Projects don’t feel like diverging snapshots anymore. They feel like instances of a shared standard that stays current.

The Day-to-Day Experience

Working with a Copier-generated project feels like working with any well-structured Python project, except everything is already configured the way you like it. The Makefile commands are muscle memory at this point. make all-check before commits. make tests before pushing. make clean when things get messy.

Pre-commit hooks run automatically on every commit, catching issues before they reach CI. Ruff handles formatting and linting. Mypy enforces type safety—I keep it strict because I’ve learned the hard way that type annotations save time debugging later. Prek manages all these hooks with better performance than the Python-based pre-commit. Commitizen validates commit messages to keep history clean.

The config pattern in src/config.py uses Pydantic Settings to load environment variables with validation. Every project has the same approach: settings class, environment file, type-safe access. No more wondering how the configuration works in this particular project.

Testing is set up with pytest, paths configured correctly, fixtures ready to use. The structure assumes you’ll have unit tests and integration tests in separate directories.

Compared to Cookiecutter, the differences are subtle at generation time but significant over time. Cookiecutter generates cleaner initial output because it’s not tracking metadata. Copier adds .copier-answers.yml and keeps a reference to the template source. That overhead is small—one file, a few lines—but it enables the update workflow.

For one-off projects you’ll never touch again, Cookiecutter is perfectly fine. For projects you maintain, or team templates that need to stay current, Copier’s update mechanism is worth the small metadata cost.

Running It Yourself

Getting started takes two minutes. Install Copier via uv:

uv tool install copierGenerate a project from the template:

copier copy ~/path/to/copier-template ~/path/to/my-new-project --trustThe --trust flag is required because the template runs tasks (shell commands) during generation. Answer the prompts: project name, module name, Python version, description. Copier creates the project, runs the initialization tasks, and you’re done. The project is already a git repository, already pushed to GitHub, already has dependencies installed.

To test the update workflow, make a change to your template:

cd ~/path/to/copier-template

# Add something to the Makefile

echo “test-update:” >> Makefile

echo “\t@echo ‘Testing template updates!’” >> Makefile

# Commit and tag

git add .

git commit -m “feat: Add test-update command”

git tag v0.2.0

git push origin main --tagsNow update your project:

cd my-new-project

copier update --trust --skip-tasksCopier detects the version change (v0.1.0 → v0.2.0), shows you the Makefile diff, and asks if you want to apply it. Review, accept, commit. The template improvement propagated to your project in seconds.

Templates as Living Documents

The shift from Cookiecutter to Copier changed how I think about project initialization. Templates aren’t just about getting started fast. They’re about maintaining consistency as your practices evolve.

Before Copier, improving my development workflow meant accepting that old projects would stay outdated. After Copier, improvements propagate. The template becomes a central place where you refine your practices, and all projects benefit.

This matters more as you create more projects. Two projects? Manual updates are fine. Ten projects? Updates become tedious. Twenty projects? You stop updating altogether and accept inconsistency.

Copier makes the cost of maintaining consistency nearly zero. Update the template, run copier update in each project, review changes, done. The projects I started months ago now have the same tooling improvements as projects I started last week.

That’s the real win. Not faster project generation—Cookiecutter is fast enough. It’s that your projects can mature with your understanding of good practices instead of being frozen in time.

Try it. Fork the template. Generate a project. Improve the template. Update the project. When you see your improvement propagate with one command, you’ll understand why this matters.

The code is on GitHub. Questions? Improvements? I’d like to hear about them.

Appreciate you being here,

Benito

I don’t write just for myself—every post is meant to give you tools, ideas, and insights you can use right away.

🤝 Got feedback or topics you’d like me to cover? I’d love to hear from you. Your input shapes what comes next!